Are Shark Populations Actually Declining in Florida?

LET’S DIVE DEEPER

Sharks are present in our 400 million year old fossil records. They have survived 5 mass extinction events, outliving dinosaurs. New species are discovered every year, adding to the 1,000+ of already identified sharks and rays. But today, shark and ray populations are in steep decline due to overfishing and bycatch. Some are face-to-face with extinction. It is estimated that numerous prevalent, larger shark species have been decimated by 74-92% since the 1960s. Roughly one third of shark and ray species are classified at the level of, or higher than, “Near Threatened.” Not to mention, nearly half of all shark and ray species are listed as “Data Deficient.” Like them or not, the ocean needs sharks, and we need the ocean. Without them, the stable ecosystem balance that they have kept for millions of years will collapse. It is without a doubt a global phenomenon, but we get asked quite often, is this also happening to our sharks in Florida? The short answer is yes.

As we unpack this question, there are a couple of Florida-specific factors to keep in mind as we discuss shark populations:

Many of the shark species fished in Florida waters, both state and federal, are highly migratory, traveling across many jurisdictions. In other words, licensed federal and state commercial fishermen are catching local and migrating sharks.

The shark species that are most commonly targeted for their fins are the same species that are the biggest attractions for the dive industry (hammerhead, tiger, bull, lemon, and so on).

The FWC does not track which species are caught for their fins. We will dive into this in the “Current Fishing Regulations” section.

Perhaps of the most important, but overlooked, is the fact that we are basing our current assessments of populations off of a skewed starting point. This is covered in detail in the following section.

SHIFTING BASELINE ARGUMENT

Claims that US shark fishing is managed sustainably is based on the notion that some species are in recovery. But these numbers are mainly determined by fisheries data from the early 90’s as a starting point, when many species were already depleted. In fact, most coastal shark species underwent sever exploitation before 1993. Additionally, the history of Florida’s sharks is a sad example of over-exploitation resulting in a shifting baseline. In the 1920’s and 30’s there were at least two significant shark processing factories in Florida. By 1946, at the height of its production, the factory in Martin County processed 25,000+ ‘tigers of the sea’ per year. The factory in the Florida Keys reported processing 100 sharks per day, on average. These factories eventually closed when cheaper sources of vitamin A came on the market, but the sharks were likely already fished out of the area. Still today, in these same waters, it can take days for researchers to find a single large shark.

“For many species a historical perspective is obscured by a reliance on recent data in analyses” (Baum et al 2004). According to research conducted in the Gulf of Mexico, it is estimated that silky and oceanic whitetip sharks were once the most commonly caught open-ocean species. Today, silky sharks have declined by 90%, and oceanic whitetips by 99%, a major sign that our perceptions must have gotten used to a new normal, a shifting baseline. Why else would be be able to look at these numbers and not ring the alarm bells? To add some context, pelagic sharks in the Gulf encountered a steep decline in populations due to to the onset of industrialized pelagic fisheries.

Now let’s look at the Florida Keys. In 2007, a study was conducted where researchers found that fishermen that used the same practices as those in the 1930’s yielded significantly fewer sharks. Gillnet fishermen in the 30’s caught roughly 100 sharks every day, but without changing anything, they only catch 2 per day. Also, hammerhead sharks and smalltooth sawfish were previously reported as very commonly caught, but today they are rare catches.

NOAA SHARK STOCK ASSESSMENT, SHARK FISHING QUOTAS AND RETENTION LIMITS

A lot of research on declining coastal and pelagic shark populations has been conducted in the North-West Atlantic ocean, ranging from 64% to 80%. Keep in mind that the majority of these figures are only based off of the past 30 years. In the overall history of shark populations, these figure could increase drastically. Here are some more specific numbers:

Hammerhead sharks - 89% decline since 1986

White sharks - 79% decline (no date specified)

Tiger sharks - 65% decline since 1986

Coastal species - 61% decline since 1992

Thresher sharks - 80% decline (no date specified)

Blue sharks - 60% decline (no date specified)

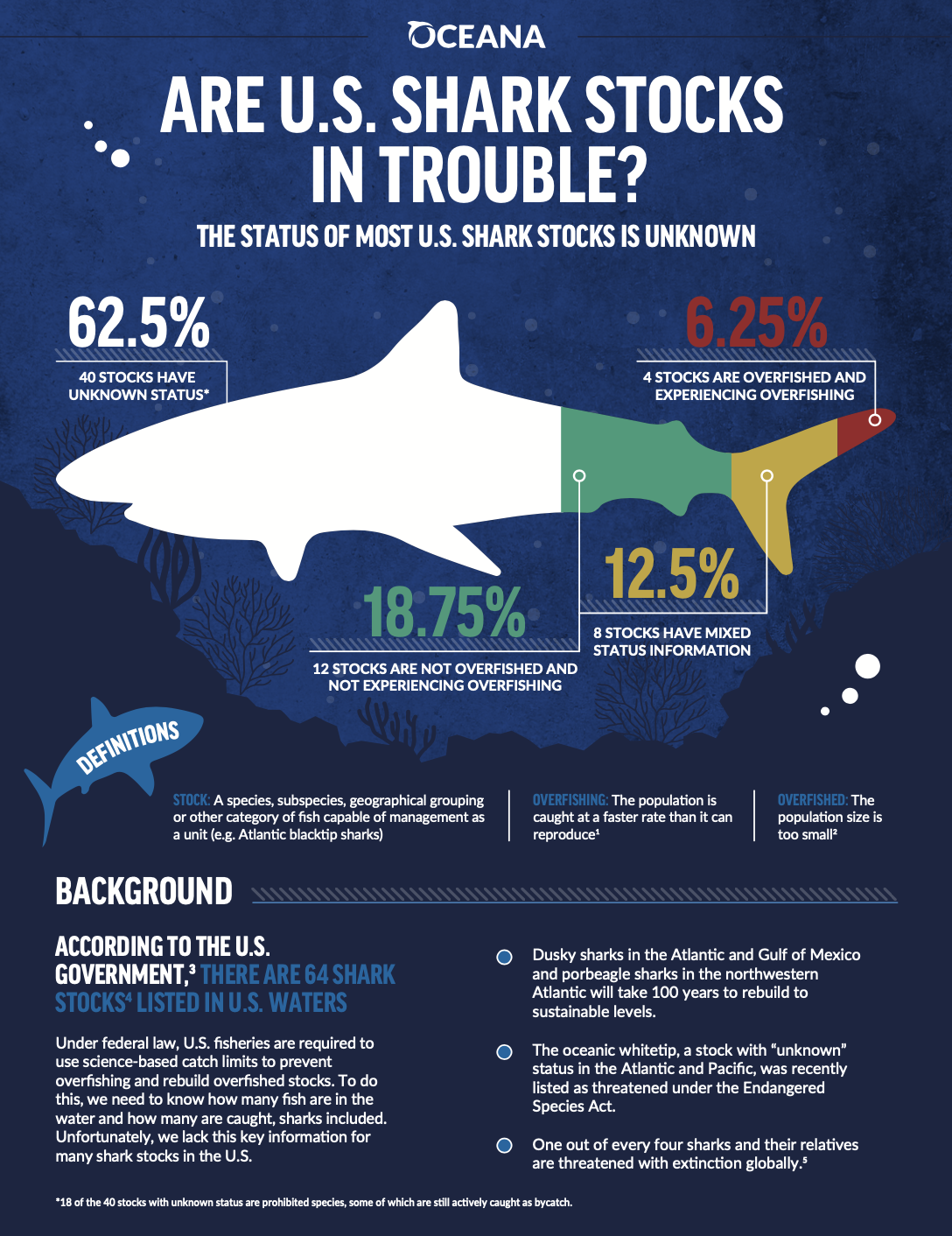

We’ve seen numbers like these before, but now we are going to explain NOAA’s recent stock assessment of 64 shark stocks (see photos above):

40 (62.5%) stocks have “unknown” overfished/fishing status

12 (18.75%) are not overfished or experiencing overfishing

4 (6.25%) are overfished or experiencing overfishing

8 (12.5%) have mixed status information

The take-away is that more than 60% of the assessed shark stocks are completely unknown if they are currently overfished or being overfished. This does not necessarily mean that this portion of shark stocks have not been assessed, although many have not. Sometimes the assessment can have so much uncertainty that it is not fit to be used. For example, the oceanic whitetip, that has been highlighted in other research as declining as much as 90%, but NOAA has the species listed as “unknown.” How is this acceptable?

CURRENT FISHING REGULATIONS

To further complicate endangered species tracking and the fin trade issue, the Fish and Wildlife Commission does not track which species are caught for their fins. According to the FWC, large coastal sharks are mostly protected in State waters, yet in Federal waters, a commercial vessel can catch up to 45 of them per day. Small coastal sharks do not even have a limit, unless the FWC puts in place a seasonal quota. Pelagic, or open water sharks, have even less protection than that.

Based off of what we discussed in NOAA’s stock assessment section, let’s dive a bit deeper into their 2020 commercial Atlantic shark fishing quotas. According to their species assessments, they start the year with no additional quotas, other than 45 per vessel per day according to permit limits. This 45 number, again, is just for large coastal sharks. Under NOAA, small coastal sharks, often referred to as “non-blacknose”, and most pelagic have no catch limits. In other words, dozens of shark species are veiled by the designation of “non-blacknose”, “non-sandbar”, “large coastal sharks”, “small coastal sharks”, and “pelagic sharks”.

Once back at the port in Florida, there are major data reporting discrepancies, allowing endangered and threatened shark species to slip through the cracks of the fin trade. In the most recently available year, 2016, the NMFS reported 591,871 pounds of shark. Of those, nearly 1/3 (195,661 pounds) were unidentified species. It is impossible to know if endangered sharks were amongst this data.